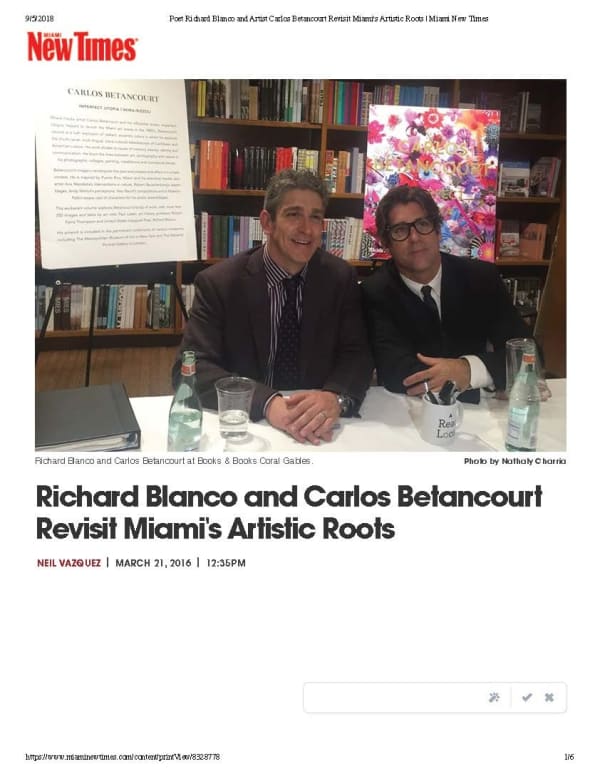

Richard Blanco and Carlos Betancourt Revisit Miami's Artistic Roots.

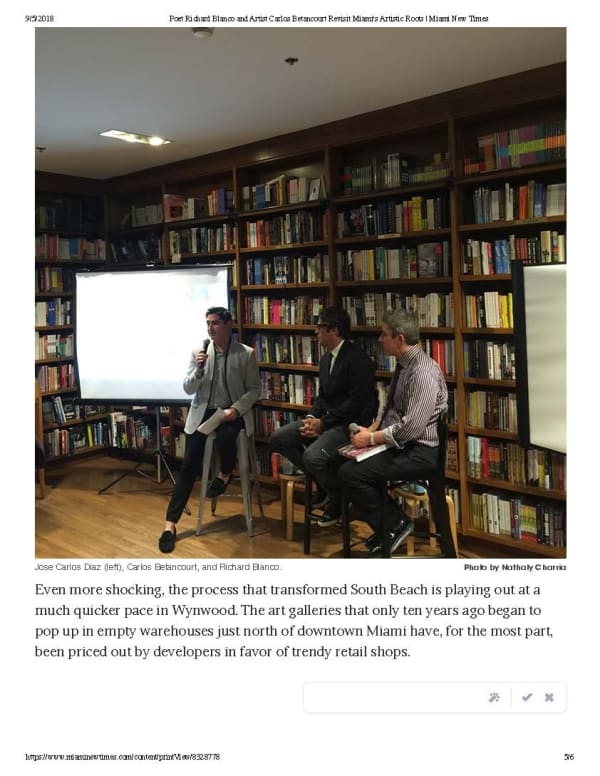

The pair met at one of artist John Bailly's notorious underground parties. At the time, Blanco was fresh out of engineering school. Betancourt, however, was a fixture on the local scene and a larger-than-life character who lived and breathed his work.

"To me, to be an artist is to wake up and be able to do whatever it is you want," the bespectacled Betancourt explains. "In my original studio on Lincoln Road, I paid $280 a month for the space and had to shower with a hose, but I loved it because I was free."

Their relationship grew out of a mutual need: Blanco gained confidence from Betancourt's strong sense of self, and the aspiring scribe lent his lyrical prose to Betancourt's highly stylized collages, sculptures, and photographs. It's a dialogue that continues today.

Betancourt's book reveals that both men's works draw from the same sensibility. The images recalled in Blanco's poems "América" and "Photoshop" form an elaborate web of the same nostalgia-soaked objects Betancourt employs in his works. The fractured nature of a Cuban-American identity lies at the heart of their collective fascination. Raised by Cuban-exile parents, they draw from similar experiences growing up in a cultural diaspora. Blanco went on to champion those same ideas at President Barack Obama's 2013 inauguration as the first gay Latino immigrant to serve as an inaugural poet.

Through their work, both artists try to piece together their fractured identities. In Betancourt's 2007 installation "Re-Collections III," the artist displayed his extensive collection of pre-1980s Christmas ornaments. The pieces were emotionally charged artifacts because Betancourt had no Christmas ornaments in his home when he first moved from Cuba to Puerto Rico. As he recalls the story, tears well up.

Apart from being a survey into his varied projects throughout the years, Imperfect Utopia is a lament for a Miami lost to overdevelopment. The same movement of local business owners that turned Lincoln Road from a rundown promenade into a thriving hot spot now wince at the current state of the pedestrian mall. Lincoln Road, with department stores displacing cultural institutions such as ArtCenter, is a sad shadow of its former self.

"It will never be like it was," Betancourt bemoans. "Back then, there was a real underground scene where people went to clubs and bars to find themselves, not because they heard about it from Twitter or Instagram and thought it was hip, which is a word I hate."

Even more shocking, the process that transformed South Beach is playing out at a much quicker pace in Wynwood. The art galleries that only ten years ago began to pop up in empty warehouses just north of downtown Miami have, for the most part, been priced out by developers in favor of trendy retail shops.

"I love the idea that art can even do that," Blanco says of the transformative effect artists had on South Beach and more recently Wynwood and Little River. "But we have to strike a balance with things like rent stabilization that offset real-estate development."

For several years, both artists have been working on different sides of the same mountain and slowly chipping away at the big questions that continue to puzzle them: What does it mean to be Cuban-American? How does memory form an active part of the immigrant diaspora? And can a single individual hold more than one distinct identity? The answers to those questions form an integral part of Miami's diverse culture and its people.